“Do you see yonder cloud that’s almost in shape of a camel? By th’mass, and ‘tis like a camel indeed. Methinks it is like a weasel”. An exhausted student turned another page of her copy of Hamlet to finish up the homework for her literary criticism class. “What was the author trying to convey in this quote from Act 3, Scene 2?”, the question popped out at her. ‘Seriously, who cares what Shakespeare had in mind?’, she thought. ‘Why can’t I just write what I think?’ Begrudgingly, fully aware that such rebellious ideas are not entertained in Mrs Mckinnon’s second period class, she tried to put herself in the shoes of the most celebrated English writer of all time. As it turns out, she is certainly not the only person to have the same train of thought. French literary theorist Roland Barthes certainly agreed.

In his seminal essay ‘The Death of the Author’, Barthes argued that the interpretation of the author is merely one point of view, and does not get an automatic precedence over others’ opinions on the piece. This was in stark contrast to the ideas of the prevalent traditional literary criticism, which heavily incorporated the intentions and biographical context of the author in interpreting the text. Barthes dissented and believed that a piece, when complete, was independent from its author, and the ‘origin’ of its meaning lied exclusively with the impressions of the reader. This technique of understanding a piece of work, independent from the author’s original intentions, does not have to be restricted to literature, of course. It can broadly be applied to anything that is consumed by an audience, following its ‘creation’. Although this blatant disregard for the author may have no place in Mrs Mckinnon’s literary criticism class, it certainly is not out of place in the real world. Indeed, many great ideas have evolved from their prototypes due to the impertinence of its consumers. Some of these alterations have even improved the original and have shaped the world for the better.

Render unto Caesar: Secularism in the Bible

Religious texts are notorious for being ambiguous in some of its teachings and the Bible is no exception to this norm. Differing interpretations have resulted in creating thousands of denominations, and both abolitionists and defenders of slavery have invoked the book to defend their respective positions. However, being a fertile ground for differing understandings is perhaps not such a bad thing after all. One of the most discussed portions of the Bible is when Jesus was posed a difficult question by his enemies trying to trap him (appears in Matthew 22: 15-22, Mark 12: 13-17 & Luke 20: 20-26). Keeping in mind Jesus’ teachings about the Kingdom of Heaven and his apathy to worldly politics, they asked him if people should be paying taxes to the Roman authorities. This immediately put Christ in a Catch-22 situation as if he opposed taxation, he could have been immediately arrested for treason. Taking the alternate position was also disadvantageous as it would imply hypocrisy and go against everything he taught. He famously replied, ‘Render unto Caesar*1 the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s’.

Although brilliant in dodging the bullet, this response has generated many interpretations, across the centuries. Many have pondered what Jesus (or the author) exactly meant by this retort. One popular conclusion is that Jesus was acknowledging that religion and worldly duties should be kept separately, and that both these non-contradictory facets are essential for a wholesome life. As already stated, many have had differing views, along with rejecting the aforementioned position. Regardless of what the original message was, the former interpretation, along with the people with this view, has been extremely important for the Western World. Many people believe that this potential reading of the Bible has been instrumental in shaping the concept of secularism in the West. Secularism (defined as the ‘separation of church from the state’) means that the government cannot endorse or oppose any particular religious belief. Although similar concepts have appeared interspersed throughout history, the United States was the first modern republic to incorporate this concept into its legal system. This vital cog in the constitution has allowed the country to flourish and has protected the rights of many to hold different religious beliefs (or to hold none at all). Although many of them were Christians, the founding fathers of America still found it imperative to include secularistic values in the process. Thomas Jefferson, a Christian deist, for instance, wrote letters indicating his beliefs that religion should be purely a matter ‘between Man & his God’. Some critics have also argued that the absence of a similar verse in the Quran is possibly one of the reasons that secularism is not as well received in the Islamic world as it is in the West. The readers’ freedom to give meaning to this Biblical verse could thus be argued, at best, partially inspired the concept of secularism in the West, and at worst, created a group of people who were receptive to the concept when it was introduced.

Memes: From Dawkins to Reddit

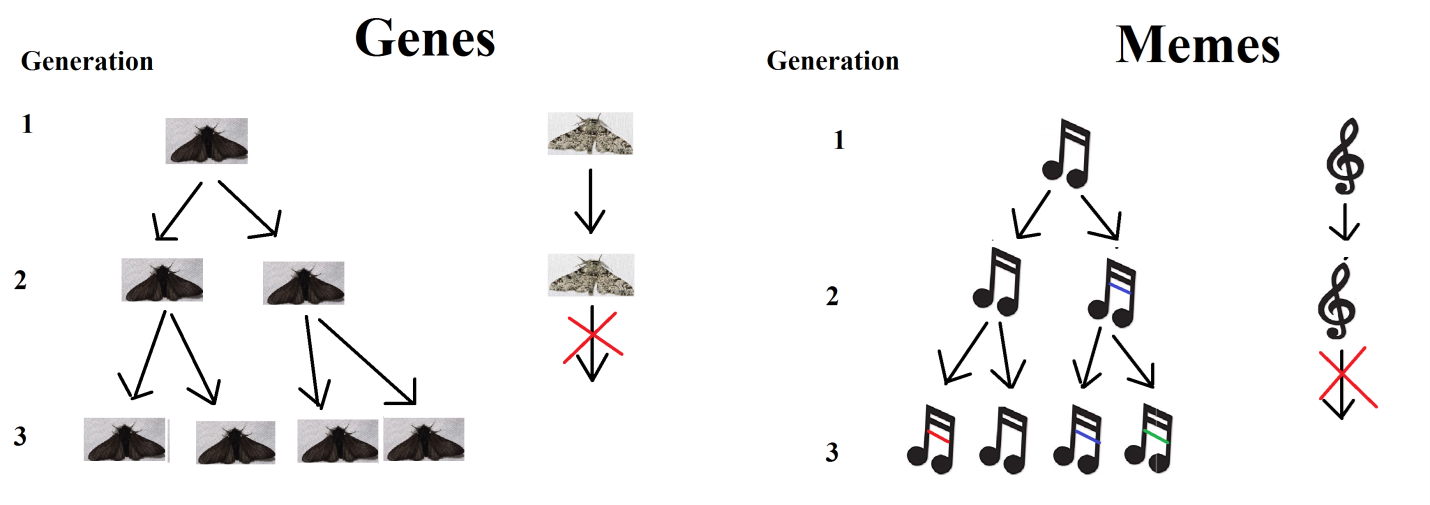

The reader’s disregard for the author’s initial intention behind a concept could also be applied to the online memes spreading across the internet. Memes, a concept originally coined by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins in his book ‘The Selfish Gene’ (1976), were used to describe cultural ideas that spread across people, with little changes between each transfer. Although the whole book was dedicated to genes (units of hereditary information, accurately transferred from parent to offspring), he introduced memes to draw a parallel to genes, and to show that natural selection could act on other things as well. Thus, if an element of culture, or a particular behavior (examples could include anything from a specific tune that is hummed, a certain word, a particular way to perform a task, a belief that is held, a unique style of fashion etc.) was deemed ‘superior’ to its competing elements, then these ‘memes’ will be more frequently passed on from one person to another, by means of imitation. This would result in the increased survival of the selected memes, thus essentially passing it on further. This is especially analogous to genes, which are also selectively passed on through generations, depending on if they confer an advantage to its possessor. The memes, or genes, that are not passed on, die out from the population.

Although Dawkins merely used his meme concept to suggest other potential avenues for natural selection, the idea was embraced by the online community, who shared images, videos, text etc., calling them ‘memes’. Dawkins himself has publicly questioned whether this mass sharing on the internet could completely fall under the definition of the concept he described. Although there certainly are aspects of his original ideas in this virtual phenomenon, he has pointed out that the rapid modifications that could happen in between each ‘share’ may disqualify at least a portion of the memes from fitting into his concept of a meme. Nevertheless, the cyber memes are still going strong, with many of them going viral every second, further increasing the enjoyability of the internet. The majority of the creators or sharers of these memes are incidentally following Barthes’ principle of the ‘Death of the Author’ as they have their own interpretation of the concept, unaware of its origin story as it appeared in the 1976 Dawkins book.

The Vertigo Effect

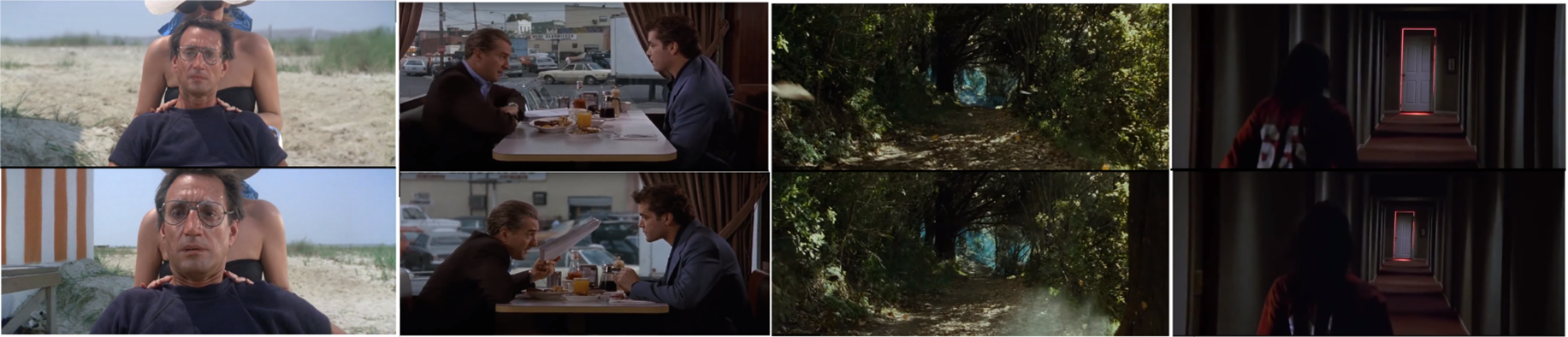

Similar examples can be found in other media as well. When filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock was planning the climax of his film Vertigo (1958), he wanted to convey the acrophobia (fear of heights) and vertigo (the sensation of the world spinning around, and a loss of balance) that the protagonist felt during the scene. To achieve this, Hitchcock, with the help of second unit cameraman Irmin Roberts, invented a new filmmaking technique, where the camera moved forwards, while simultaneously zooming out. This created the impression that the background moved away from the steady foreground, thus distorting the perspective of the viewer. In this case, the protagonist, detective John “Scottie” Ferguson, feels that the ground gets farther away from him than it actually is, and the viewer shares his disconcerting dread. It is a truly stunning cinematic achievement, and has been celebrated as such.

This effect, known as the Vertigo effect (also known as the Dolly Zoom, or Zolly), has been taken up by other filmmakers as well. Although Hithcock had invented and used the technique for the aforementioned reasons, many realized that it could be used in different contexts, to enhance their own narratives. When Steven Spielberg used the method in Jaws (1975) to enhance his character’s horror at an impending shark attack, Martin Scorsese used it in his famous ‘diner scene’ in Goodfellas (1990) to mirror the subtle tension in the conversation and to show the protagonist’s world closing in on him. The effect’s physical distortion, and the perception it creates in the viewers, also did not escape filmmakers’ attention, as shown in The Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring (2001). Peter Jackson uses this technique brilliantly to make the forest opening appear closer to Frodo, who is on the run, escaping from the Black riders. It creates the illusion that the opening is becoming a portal, from which the riders could appear any second, increasing the anxiety of the audience. The contrasting effect (by zooming and moving the camera in the opposite directions) was utilized by Tobe Hooper in Poltergeist (1982), where he makes the doorway at the end of the hall appear to move away from his character, thus making it perpetually out of reach of her.

Thus, it could be argued that by not rigidly following the source, and by ignoring the preliminary reason why the effect was developed by the creator, these directors helped in enhancing the utility of the method, and took filmmaking to the next level in the process.

CRISPR-Cas9: Ctrl + X, Ctrl + V the Genome

Although Barthes’ philosophy applies to works created by people, the concept can be loosely extended to other cases as well. For instance, many biological phenomena that have evolved to its present state can be utilized for entirely different functions. One such system that scientists have successfully harnessed recently is the CRISPR-Cas9.

CRISPR (which stands for Clustered Regularly-Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) is a short stretch of DNA found as part of the bacterial*2 immune system. It is very similar to antibodies in humans insofar as both consist of using a portion of the pathogens invading the body, in order to ‘remember’ them for future attacks. When bacteriophages (viruses that attack bacteria) invade, enzymes of the bacterium destroy the virus and incorporate some of its DNA into its own. This integrated viral DNA, combined with all such DNA that the bacterium collected throughout its lifetime, are what appears as clustered, regular, interspaced, short repeats on its genome (and lends CRISPR its name). If bacteriophages with the same DNA attack the bacterium again, special attack proteins known as Cas9 (CRISPR associated protein 9) use the stored DNA as a template, and launch a defence. Cas9 acts as a ‘molecular scissors’ and if the DNA of the attacking virus matches the template DNA previously stored by the bacterium, it chops up the pathogen, neutralizing the threat.

Although scientists knew about this innate immune mechanism in bacteria, Dr Jennifer Doudna & Dr Emmanuelle Charpentier reimagined this system to achieve something completely different. Despite its original evolutionary purpose as a defence mechanism in bacteria, they realized that the CRSIPR-Cas9 machinery could be used as a gene editing tool by manipulating the template strand presented to the Cas9 protein. Since the protein cut the DNA that matched the template that it carried, it meant that any part of an organism’s DNA could be targeted as long as the appropriate sequence was provided as the template. The specificity of this targeting was extremely useful as with this system, any part of the genome could be selectively removed, and fragments could be added if required.

The potential of this editing system is enormous as genes carry the instructions required to make proteins, which in turn, perform all bodily functions. Thus, the ability to manipulate selected genes could theoretically cure any medical condition with a genetic component, slow down or even stop aging, improve crop quality & yields, make better antibiotics and more. Needless to say, it also opens up a massively big can of worms, including biological warfare, a misuse of the technology for aesthetic purposes, & creating ‘designer babies’ with a customized genetic makeup, to name a few. Although there may not have been any actual “author’s death” in this example, the remodeling of the CRISPR-Cas9 system into a gene editing tool, from its original evolved function, is certainly a victory to the maverick approach supported by Barthes.

Some of the examples that are cited in this article may feel a stretch too far to be linked to the ideas elucidated in ‘The Death of the Author’. However, by extending Barthes’ position on the matter, it could be argued that my interpretations of his essay are more valid than the author’s own views. A lot of such ideas may seem similar to other concepts that frequent modern discourse. Indeed, movements such as postmodernism (the school of thought which argues that there are no objective/universal truths) have been heavily influenced by Barthes and his ideas. Although there certainly are benefits to thinking outside the box and in questioning conventions as seen in this article, there are also caveats in rejecting established positions prima facie. It certainly is true that an objectively absolute understanding of things may be beyond human faculties. However, that does not automatically mean that all interpretations of reality should be equally valid. While the Barthesian postmodern worldview may have utility in subjective fields such as philosophy, arts, architecture and literature, it can sometimes be adverse in science, which relies on evidence. In the CRISPR example that was looked at, it should be stressed that the reshaping of the system to a gene editing tool was achieved on the back of numerous careful studies, and not just on the basis of ‘armchair theorizing’. Whenever possible, claims backed by evidence should certainly be given a preference to competing interpretations that are not verified. This lack of evidence on their side, for instance, is precisely why the anti vaccination campaigns pose serious consequences for the society. Thus, critical thinking should not start by assuming that the author deserves to die. Nor should it end with their murder. It should ideally follow the trail of evidence, improving the original in the process. The ‘Death of the Author’, in other words, should be the ‘Birth of the Reader’.

*1 Title used by Roman emperors at the time

*2 CRISPR has been identified in prokaryotes (single celled organisms, including archaea and bacteria). Similarly, bacteriophages attack prokaryotes. This article only mentioned bacteria for simplicity.